Ring (mathematics)

In mathematics, a ring is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with two binary operations (usually called addition and multiplication), where each operation combines two elements to form a third element. To qualify as a ring, the set together with its two operations must satisfy certain conditions—namely, the set must be an abelian group under addition and a monoid under multiplicationa[›] such that multiplication distributes over addition. One of the most common examples of a ring is the set of integers endowed with its natural operations of addition and multiplication. Certain variations of the definition of a ring are sometimes employed, and these are outlined later in the article.

While the operations of a ring are familiar from many mathematical structures, such as number systems or the integers for example, they are also very general in the sense that they take a broad variety of mathematical objects into account. This allows one to handle entities of very different mathematical origins in a flexible way, while retaining essential structural aspects of many objects in abstract algebra and beyond. The ubiquity of rings makes them a central organizing principle of contemporary mathematics. The branch of mathematics that studies rings is known as ring theory.[1]

Rings share a fundamental kinship with number theory and linear algebra. The former is responsible for various analogues of number-theoretic theorems in ring theory—for instance, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic translates to a certain special class of rings known as unique factorization domains. The latter is responsible for the rich theory of algebras, including, but not restricted to, matrix rings. This theory of matrix rings, for example, is a striking consequence of the ways in which noncommutative ring theory may be used to understand fundamental physical laws underlying special relativity and symmetry phenomena in molecular chemistry.

The concept of a ring first arose from attempts to prove Fermat's last theorem, starting with Richard Dedekind in the 1880s. After contributions from other fields, mainly number theory, the ring notion was generalized and firmly established during the 1920s by Emmy Noether and Wolfgang Krull.[2] Modern ring theory—a very active mathematical discipline—studies rings in their own right. To explore rings, mathematicians have devised various notions to break rings into smaller, better-understandable pieces, such as ideals, quotient rings and simple rings. In addition to these abstract properties, ring theorists also make various distinctions between the theory of commutative rings and noncommutative rings—the former belonging to algebraic number theory and algebraic geometry. A particularly rich theory has been developed for a certain special class of commutative rings, known as fields, which lies within the realm of field theory. Likewise, the corresponding theory for noncommutative rings, that of noncommutative division rings, constitutes an active research interest for noncommutative ring theorists. Since the discovery of a mysterious connection between noncommutative ring theory and geometry during the 1980s by Alain Connes, noncommutative geometry has become a particularly active discipline in ring theory.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Definition and illustration

First example: the integers

The most familiar example of a ring is the set of all integers, Z, consisting of the numbers

- ..., −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ...[3]

together with the usual operations of addition and multiplication. These operations satisfy the following properties:

- The integers form an abelian group under addition; that is:

- Closure axiom for addition: Given two integers a and b, their sum, a + b is also an integer.

- Existence of additive identity: For any integer a, a + 0 = 0 + a = a. Zero is called the identity element of the integers because adding 0 to any integer (in any order) returns the same integer.

- Commutativity of addition: For any two integers a and b, a + b = b + a. So the order in which two integers are added is irrelevant.

- Associativity of addition: For any integers, a, b and c, (a + b) + c = a + (b + c). So, adding b to a, and then adding c to this result, is the same as adding c to b, and then adding this result to a.

- Existence of additive inverse: For any integer a, there exists an integer denoted by −a such that a + (−a) = (−a) + a = 0. The element, −a, is called the additive inverse of a because adding a to −a (in any order) returns the identity.

- The integers form a multiplicative monoid (a monoid under multiplication); that is:

- Closure axiom for multiplication: Given two integers a and b, their product, a · b is also an integer.

- Associativity of multiplication: Given any integers, a, b and c, (a · b) · c = a · (b · c). So multiplying b with a, and then multiplying c to this result, is the same as multiplying c with b, and then multiplying a to this result.

- Existence of multiplicative identity: For any integer a, a · 1 = 1 · a = a. So multiplying any integer with 1 (in any order) gives back that integer. One is therefore called the multiplicative identity.

- Multiplication is distributive over addition : These two structures on the integers (addition and multiplication) are compatible in the sense that

- a · (b + c) = (a · b) + (a · c), and

- (a + b) · c = (a · c) + (b · c)

- for any three integers a, b and c.

Formal definition

There are some differences in exactly what axioms are used to define a ring. Here one set of axioms is given, and comments on variations follow.

A ring is a set R equipped with two binary operations + : R × R → R and · : R × R → R (where × denotes the Cartesian product), called addition and multiplication. To qualify as a ring, the set and two operations, (R, +, · ), must satisfy the following requirements known as the ring axioms.[4]

- (R, +) is required to be an abelian group under addition:

-

1. Closure under addition. For all a, b in R, the result of the operation a + b is also in R.c[›] 2. Associativity of addition. For all a, b, c in R, the equation (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) holds. 3. Existence of additive identity. There exists an element 0 in R, such that for all elements a in R, the equation 0 + a = a + 0 = a holds. 4. Existence of additive inverse. For each a in R, there exists an element b in R such that a + b = b + a = 0 5. Commutativity of addition. For all a, b in R, the equation a + b = b + a holds.

- (R, ·) is required to be a monoid under multiplication:

-

1. Closure under multiplication. For all a, b in R, the result of the operation a · b is also in R.c[›] 2. Associativity of multiplication. For all a, b, c in R, the equation (a · b) · c = a · (b · c) holds. 3. Existence of multiplicative identity.a[›] There exists an element 1 in R, such that for all elements a in R, the equation 1 · a = a · 1 = a holds.

- The distributive laws:

-

1. For all a, b and c in R, the equation a · (b + c) = (a · b) + (a · c) holds. 2. For all a, b and c in R, the equation (a + b) · c = (a · c) + (b · c) holds.

This definition assumes that a binary operation on R is a function defined on R×R with values in R. Therefore, for any a and b in R, the addition a + b and the product a · b are elements of R.

The most familiar example of a ring is the set of all integers, Z = {..., −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ... }, together with the usual operations of addition and multiplication.[3]

Another familiar example is the set of real numbers R, equipped with the usual addition and multiplication.

Another example of a ring is the set of all square matrices of a fixed size, with real elements, using the matrix addition and multiplication of linear algebra. In this case, the ring elements 0 and 1 are the zero matrix (with all entries equal to 0) and the identity matrix, respectively.

Notes on the definition

In axiomatic theories, different authors sometimes use different axioms. In the case of ring theory, some authors include the axiom 1 ≠ 0 (that is, that the multiplicative identity of the ring must be different from the additive identity). In particular they do not consider the trivial ring to be a ring (see below).

A more significant disagreement is that some authors omit the requirement of a multiplicative identity in a ring.[5][6][7] This allows the even integers, for example, to be considered a ring, with the natural operations of addition and multiplication, because they satisfy all of the ring axioms except for the existence of a multiplicative identity. Rings that satisfy the ring axioms as given above except the axiom of multiplicative identity are sometimes called pseudo-rings. The term rng (jocular; ring without the multiplicative identity i) is also used for such rings. Rings which do have multiplicative identities, (and thus satisfy all of the axioms above) are sometimes for emphasis referred to as unital rings, unitary rings, rings with unity, rings with identity or rings with 1.[8] Note that one can always embed a non-unitary ring inside a unitary ring (see this for one particular construction of this embedding).

There are still other more significant differences in the way some authors define a ring. For instance, some authors omit associativity of multiplication in the set of ring axioms; rings that are nonassociative are called nonassociative rings. In this article, all rings are assumed to satisfy the axioms as given above unless stated otherwise.

Second example: the ring Z4

Consider the set Z4 consisting of the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3 where addition and multiplication are defined as follows (note that for any integer x, x mod 4 is defined to be the remainder when x is divided by 4):

- For any x, y in Z4, x + y is defined to be their sum in Z (the set of all integers) mod 4. So we can represent the additive structure of Z4 by the left-most table as shown.

- For any x, y in Z4, x ⋅ y is defined to be their product in Z (the set of all integers) mod 4. So we can represent the multiplicative structure of Z4 by the right-most table as shown.

| · | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| + | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

It is simple (but tedious) to verify that Z4 is a ring under these operations. First of all, one can use the left-most table to show that Z4 is closed under addition (any result is either 0, 1, 2 or 3). Associativity of addition in Z4 follows from associativity of addition in the set of all integers. The additive identity is 0 as can be verified by looking at the left-most table. Given an integer x, there is always an inverse of x; this inverse is given by 4 - x as one can verify from the additive table. Therefore, Z4 is an abelian group under addition.

Similarly, Z4 is closed under multiplication as the right-most table shows (any result above is either 0, 1, 2 or 3). Associativity of multiplication in Z4 follows from associativity of multiplication in the set of all integers. The multiplicative identity is 1 as can be verified by looking at the right-most table. Therefore, Z4 is a monoid under multiplication.

Distributivity of the two operations over each other follow from distributivity of addition over multiplication (and vice-versa) in Z (the set of all integers).

Therefore, this set does indeed form a ring under the given operations of addition and multiplication.

Properties of this ring

- In general, given any two integers, x and y, if x ⋅ y = 0, then either x is 0 or y is 0. It is interesting to note that this does not hold for the ring (Z4, +, ⋅):

-

- 2 ⋅ 2 = 0

- although neither factor is 0. In general, a non-zero element a of a ring, (R, +, ⋅) is said to be a zero divisor in (R, +, ⋅), if there exists a non-zero element b of R such that a ⋅ b = 0. So in this ring, the only zero divisor is 2 (note that 0 ⋅ a = 0 for any a in a ring (R, +, ⋅) so 0 is not considered to be a zero divisor).

- A commutative ring which has no zero divisors is called an integral domain (see below). So Z, the ring of all integers (see above), is an integral domain (and therefore a ring), although Z4 (the above example) does not form an integral domain (but is still a ring). So in general, every integral domain is a ring but not every ring is an integral domain.

Third example: the trivial ring

If we define on the singleton set {0}:

0 + 0 = 0

0 × 0 = 0

then one can verify that ({0}, +, ×) forms a ring known as the trivial ring. Since there can be only one result for any product or sum (0), this ring is both closed and associative for addition and multiplication, and furthermore satisfies the distributive law. The additive and multiplicative identities are both equal to 0. Similarly, the additive inverse of 0 is 0. The trivial ring is also a (rather trivial) example of a zero ring (see below).

Basic concepts

Subring

Informally, a subring of a ring is another ring that uses the "same" operations and is contained in it. More formally, suppose (R, +, ·) is a ring, and S is a subset of R such that

- for every a, b in S, a + b is in S;

- for every a, b in S, a · b is in S;

- for every a in S, the additive inverse −a of a is in S; and

- the multiplicative identity '1' of R is in S.

Let '+S' and '·S' denote the operations '+' and '·', restricted to S×S. Then (S, +S, ·S) is a subring of (R, +, ·).[9] Since the restricted operations are completely determined by S and the original ones, the subring is often written simply as (S, +, ·).

For example, a subring of the complex number ring C is any subset of C that includes 1 and is closed under addition, multiplication, and negation, such as:

- The rational numbers Q

- The algebraic numbers A

- The real numbers R

If A is a subring of R, and B is a subset of A such that B is also a subring of R, then B is a subring of A.

Homomorphism

A homomorphism from a ring (R, +, ·) to a ring (S, ‡, *) is a function f from R to S that commutes with the ring operations; namely, such that, for all a, b in R the following identities hold:

- f(a + b) = f(a) ‡ f(b)

- f(a · b) = f(a) * f(b)

Moreover, the function f must take the identity element 1R of '·' to the identity element 1S of '*'.

For example, the function that maps each integer x to its remainder modulo 4 (a number in {0, 1, 2, 3}) is a homomorphism from the ring Z to the ring Z4.

A ring homomorphism is said to be an isomorphism if it is both an epimorphism and a monomorphism in the category of rings.

Ideal

The purpose of an ideal in a ring is to somehow allow one to define the quotient ring of a ring (analogous to the quotient group of a group; see below). An ideal in a ring can therefore be thought of as a generalization of a normal subgroup in a group. More formally, let (R, +, · ) be a ring. A subset I of R is said to be a right ideal in R if:

- (I, +) is a subgroup of the underlying additive group in (R, +, · ) (i.e (I, +) is a subgroup of (R, +)).

- For every x in I and r in R, x · r is in I.

A left ideal is similarly defined with the second condition being replaced. More specifically, a subset I of R is a left ideal in R if:

- (I, +) is a subgroup of the underlying additive group in (R, +, · ) (i.e (I, +) is a subgroup of (R, +)).

- For every x in I and r in R, r · x is in I.

Notes

- If k is in R, then k · R is a right ideal in R, and R · k is a left ideal in R. These ideals (for any k in R) are called the principal right and left ideals generated by k.

- If every ideal in a ring (R, +, · ) is a principal ideal in (R, +, · ), (R, +, · ) is said to be a principal ideal ring.

- An ideal in a ring, (R, +, · ), is said to be a two-sided ideal if it is both a left ideal and right ideal in (R, +, · ). It is preferred to call a two-sided ideal, simply an ideal.

- If I = {0} (where 0 is the additive identity of the ring (R, +, · )), then I is an ideal known as the trivial ideal. Similarly, R is also an ideal in (R, +, · ) called the unit ideal.

Examples

- Any additive subgroup of the integers is an ideal in the integers with its natural ring structure.

- There are no non-trivial ideals in R (the ring of all real numbers) (i.e, the only ideals in R are {0} and R itself). More generally, a field cannot contain any non-trivial ideals.

- From the previous example, every field must be a principal ideal ring.

- A subset, I, of a commutative ring (R, +, · ) is a left ideal if and only if it is a right ideal. So for simplicity's sake, we refer to any ideal in a commutative ring as just an ideal.

History

The study of rings originated from the theory of polynomial rings and the theory of algebraic integers. Furthermore, the appearance of hypercomplex numbers in the mid-nineteenth century undercut the pre-eminence of fields in mathematical analysis.

In the 1880s Richard Dedekind introduced the concept of a ring,[2] and the term ring (Zahlring) was coined by David Hilbert in 1892 and published in the article Die Theorie der algebraischen Zahlkörper, Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker Vereinigung, Vol. 4, 1897. According to Harvey Cohn, Hilbert used the term for a specific ring that had the property of "circling directly back" to an element of itself.[10]

The first axiomatic definition of a ring was given by Adolf Fraenkel in an essay in Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (A. L. Crelle), vol. 145, 1914.[11][2] In 1921, Emmy Noether gave the first axiomatic foundation of the theory of commutative rings in her monumental paper Ideal Theory in Rings.[2]

Elementary properties of rings

Some properties of rings follow directly from the ring axioms through very simple proofs.

In particular, since the axioms state that (R,+) is a commutative group, all pertinent theorems of group theory apply, such as the uniqueness of the additive identity and the uniqueness of the additive inverse of a particular element. In the same way one can prove the uniqueness of the inverse of a unit in a ring.

However, rings also have specific properties that combine addition with multiplication. In any ring (R, +, ⋅):

- For any element a, the equations a ⋅ 0 = 0 ⋅ a = 0 hold.

- If 0 = 1, the ring is trivial (that is, R has only one element).

- For any element a, the equation (−1) ⋅ a = −a holds.

- For any elements a and b, the equations (−a) ⋅ b = a ⋅ (−b) = −(a ⋅ b)

New rings from old

Quotient ring

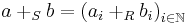

Informally, the quotient ring of a ring, is a generalization of the notion of a quotient group of a group. More formally, given a ring (R, +, · ) and a two-sided ideal I of (R, +, · ), the quotient ring (or factor ring) R/I is the set of cosets of I (with respect to the underlying additive group of (R, +, · ); i.e cosets with respect to (R, +)) together with the operations:

- (a + I) + (b + I) = (a + b) + I and

- (a + I)(b + I) = (ab) + I.

For every a, b in R.

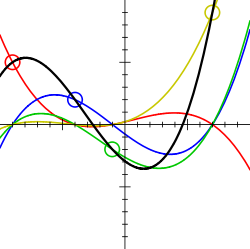

Polynomial ring

Formal definition

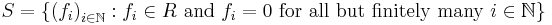

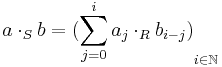

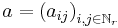

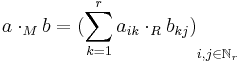

Let (R, +R, ·R) be a ring and let  where the convention that

where the convention that  is the set of all nonnegative integers, is adopted. Define +S : S × S → S and ·S : S × S → S, as follows (where

is the set of all nonnegative integers, is adopted. Define +S : S × S → S and ·S : S × S → S, as follows (where  and

and  are arbitrary elements of S):

are arbitrary elements of S):

Then (S, +S, ·S) is a ring referred to as the polynomial ring over R.

Notes

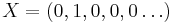

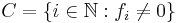

Most authors write S as R[X], where  is an element of S. This convention is adopted because if

is an element of S. This convention is adopted because if  is an element of S, and if

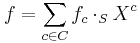

is an element of S, and if  , f can be written as a polynomial with coefficients in R, in the variable X, as follows:

, f can be written as a polynomial with coefficients in R, in the variable X, as follows:

This allows one to view S as merely the set of all polynomials over R in the variable X, with multiplication and addition of polynomials defined in the canonical manner. Therefore, in all that follows, S, denoted by R[X], shall be identified in this fashion. Addition and multiplication in S, and those of the underlying ring R, will be denoted by juxtaposition.

Matrix ring

Formal definition

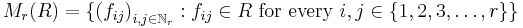

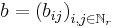

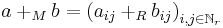

Let (R, +R, ·R) be a ring and let  . Define +M : Mr(R) × Mr(R) → Mr(R) and ·M : Mr(R) × Mr(R) → Mr(R), as follows (where

. Define +M : Mr(R) × Mr(R) → Mr(R) and ·M : Mr(R) × Mr(R) → Mr(R), as follows (where  and

and  are arbitrary elements of Mr(R)):

are arbitrary elements of Mr(R)):

Then (Mr(R), +M, ·M) is a ring referred to as the ring of r×r matrices over R.

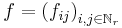

Notes

The ring Mr(R) can be viewed as merely the ring of r×r matrices over R with matrix addition and multiplication defined in the canonical manner. For given  in Mr(R), f can be identified with the r×r matrix whose (i, j)-entry is

in Mr(R), f can be identified with the r×r matrix whose (i, j)-entry is  . Therefore, in all that follows, Mr(R) and each of its elements shall be identified in this fashion. Addition and multiplication in Mr(R), and those of the underlying ring R, will be denoted by juxtaposition.

. Therefore, in all that follows, Mr(R) and each of its elements shall be identified in this fashion. Addition and multiplication in Mr(R), and those of the underlying ring R, will be denoted by juxtaposition.

Some examples of the ubiquity of rings

It is remarkable how many different kinds of mathematical objects can be fruitfully analyzed in terms of some associated ring. For instance:

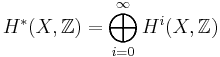

- To any topological space X one can associate its integral cohomology ring

, a graded ring. As the name suggests, there are also homology groups

, a graded ring. As the name suggests, there are also homology groups  of a space, and indeed these were defined first, as a useful tool for distinguishing between certain pairs of topological spaces, like the spheres and tori, for which the methods of point-set topology are not well-suited. Cohomology groups were later defined in terms of homology groups in a way which is roughly analogous to the dual of a vector space. To know each individual integral homology group is essentially the same as knowing each individual integral cohomology group, because of the universal coefficient theorem. However, the advantage of the cohomology groups is that there is a natural product, which is analogous to the observation that one can multiply pointwise a k-multilinear form and an l-multilinear form to get a (k + l)-mulilinear form. The importance of the ring structure in cohomology is hard to overstate: it provides the foundation for characteristic classes of fiber bundles, intersection theory on manifolds and algebraic varieties, Schubert calculus and much more.

of a space, and indeed these were defined first, as a useful tool for distinguishing between certain pairs of topological spaces, like the spheres and tori, for which the methods of point-set topology are not well-suited. Cohomology groups were later defined in terms of homology groups in a way which is roughly analogous to the dual of a vector space. To know each individual integral homology group is essentially the same as knowing each individual integral cohomology group, because of the universal coefficient theorem. However, the advantage of the cohomology groups is that there is a natural product, which is analogous to the observation that one can multiply pointwise a k-multilinear form and an l-multilinear form to get a (k + l)-mulilinear form. The importance of the ring structure in cohomology is hard to overstate: it provides the foundation for characteristic classes of fiber bundles, intersection theory on manifolds and algebraic varieties, Schubert calculus and much more. - To any group is associated its Burnside ring which uses a ring to describe the various ways the group can act on a finite set. The Burnside ring's additive group is the free abelian group whose basis are the transitive actions of the group and whose addition is the disjoint union of the action. Expressing an action in terms of the basis is decomposing an action into its transitive constituents. The multiplication is easily expressed in terms of the representation ring: the multiplication in the Burnside ring is formed by writing the tensor product of two permutation modules as a permutation module. The ring structure allows a formal way of subtracting one action from another. Since the Burnside ring is contained as a finite index subring of the representation ring, one can pass easily from one to the other by extending the coefficients from integers to the rational numbers.

- To any group ring or Hopf algebra is associated its representation ring or "Green ring". The representation ring's additive group is the free abelian group whose basis are the indecomposable modules and whose addition corresponds to the direct sum. Expressing a module in terms of the basis is finding an indecomposable decomposition of the module. The multiplication is the tensor product. When the algebra is semisimple, the representation ring is just the character ring from character theory, which is more or less the Grothendieck group given a ring structure.

- To any irreducible algebraic variety is associated its function field. The points of an algebraic variety correspond to valuation rings contained in the function field and containing the coordinate ring. The study of algebraic geometry makes heavy use of commutative algebra to study geometric concepts in terms of ring-theoretic properties. Birational geometry studies maps between the subrings of the function field.

- Every simplicial complex has an associated face ring, also called its Stanley–Reisner ring. This ring reflects many of the combinatorial properties of the simplicial complex, so it is of particular interest in algebraic combinatorics. In particular, the algebraic geometry of the Stanley–Reisner ring was used to characterize the numbers of faces in each dimension of simplicial polytopes.

Special rings and rings with additional structure

Finite ring

Given a natural number m, how many distinct rings (not necessarily with unity) have m elements? When m is prime there are only two rings of order m; the additive group of each being isomorphic to the cyclic group of order m. One is the zero ring and the other is the Galois field.

As with finite groups, the complexity of the classification depends upon the complexity of the prime factorization of m. If m is the square of a prime, for instance, there are precisely eleven rings having order m. On the other hand, there can be only two groups having order m; both of which are abelian.

The theory of finite rings is more complex than that of finite abelian groups, since any finite abelian group is the additive group of at least two nonisomorphic finite rings: the direct product of copies of  , and the zero ring. On the other hand, the theory of finite rings is simpler than that of not necessarily abelian finite groups. For instance, the classification of finite simple groups was one of the major breakthroughs of twentieth century mathematics, its proof spanning thousands of journal pages. On the other hand, any finite simple ring is isomorphic to the ring

, and the zero ring. On the other hand, the theory of finite rings is simpler than that of not necessarily abelian finite groups. For instance, the classification of finite simple groups was one of the major breakthroughs of twentieth century mathematics, its proof spanning thousands of journal pages. On the other hand, any finite simple ring is isomorphic to the ring  of n by n matrices over a finite field of order q. This follows from two theorems of Joseph Wedderburn established in 1905 and 1907.

of n by n matrices over a finite field of order q. This follows from two theorems of Joseph Wedderburn established in 1905 and 1907.

One of these theorems, known as Wedderburn's little theorem, asserts that any finite division ring is necessarily commutative. Nathan Jacobson later discovered yet another condition which guarantees commutativity of a ring:

If for every element r of R there exists an integer n > 1 such that rn = r, then R is commutative.[12]

If, r2 = r for every r, the ring is called a Boolean ring. More general conditions which guarantee commutativity of a ring are also known.[13]

The number of rings with m elements, for m a natual number, is listed under A027623 in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.

Associative algebras

An associative algebra is a ring that is also a vector space over a field K. For instance, the set of n by n matrices over the real field R has dimension n2 as a real vector space, and the matrix multiplication corresponds to the ring multiplication. For a non-trivial but elementary example consider 2 × 2 real matrices.

Lie ring

A Lie ring is defined to be a ring that is nonassociative and anticommutative under multiplication, that also satisfies the Jacobi identity. More specifically we can define a Lie ring  to be an abelian group under addition with an operation

to be an abelian group under addition with an operation ![[\cdot,\cdot]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/3587c5df5edf1176ed7afc1f20f5d8a9.png) that has the following properties:

that has the following properties:

- Bilinearity:

- for all x, y, z ∈ L.

- Jacobi identity:

- for all x, y, z in L.

- For all x in L.

Lie rings need not be Lie groups under addition. Any Lie algebra is an example of a Lie ring. Any associative ring can be made into a Lie ring by defining a bracket operator ![[x,y] = xy - yx](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/2d4099ee292ebfa424a594a8233f6a38.png) . Conversely to any Lie algebra there is a corresponding ring, called the universal enveloping algebra.

. Conversely to any Lie algebra there is a corresponding ring, called the universal enveloping algebra.

Lie rings are used in the study of finite p-groups through the Lazard correspondence. The lower central factors of a p-group are finite abelian p-groups, so modules over Z/pZ. The direct sum of the lower central factors is given the structure of a Lie ring by defining the bracket to be the commutator of two coset representatives. The Lie ring structure is enriched with another module homomorphism, then pth power map, making the associated Lie ring a so-called restricted Lie ring.

Lie rings are also useful in the definition of a p-adic analytic groups and their endomorphisms by studying Lie algebras over rings of integers such as the p-adic integers. The definition of finite groups of Lie type due to Chevalley involves restricting from a Lie algebra over the complex numbers to a Lie algebra over the integers, and the reducing modulo p to get a Lie algebra over a finite field.

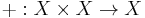

Topological ring

Let (X, T) is a topological space and (X, +, · ) be a ring. Then (X, T, +, · ) is said to be a topological ring, if its ring structure and topological structure are both compatible (i.e work together) over each other. That is, the addition map (  ) and the multiplication map (

) and the multiplication map (  ) have to be both continuous as maps between topological spaces where X x X inherits the product topology. So clearly, any topological ring is a topological group (under addition).

) have to be both continuous as maps between topological spaces where X x X inherits the product topology. So clearly, any topological ring is a topological group (under addition).

Examples

- The set of all real numbers, R, with its natural ring structure and the standard topology forms a topological ring.

- The direct product of two topological rings is also a topological ring.

Commutative rings

Although ring addition is commutative, so that for every a, b in R, a + b = b + a, ring multiplication is not required to be commutative; a · b need not equal b · a for all a, b in R. Rings that also satisfy commutativity for multiplication are called commutative rings.e[›] Formally,

Formal definition

Let (R, +, · ) be a ring. Then (R, +, · ) is said to be a commutative ring if for every a, b in R, a · b = b · a. That is, (R, +, · ) is required to be a commutative monoid under multiplication.

Examples

- The integers form a commutative ring under the natural operations of addition and multiplication.

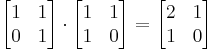

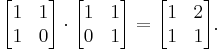

- An example of a noncommutative ring is the ring of n × n matrices over a non-trivial field K, for n > 1. In particular, the ring of all 2 × 2 matrices over R (the set of all real numbers) do not form a commutative ring as the following computation shows:

, which is not equal to

, which is not equal to

Principal ideal domains

Although rings are structurally similar to the integers, there are certain ring-theoretic properties that the integers may satisfy but a general ring may not. One such property is the requirement that every ideal in a ring be generated by a single element; that is, be a principal ideal. Formally,

Definition

Let R be a ring. Then R is said to be a principal ideal ring (abbreviated PIR), if every ideal in R is of the form a · R = {a · r | r · R}. A principal ideal domain is a principal ideal ring that is also an integral domain.

The requirement that a ring be a principal ideal domain is somewhat stronger than the other more common properties a ring may satisfy. For example, it is true that if a ring, R, is a unique factorization domain (UFD), then the polynomial ring over R is also a UFD. However, such a result does not in general hold for principal ideal rings. For example, the integers are an easy example of a principal ideal ring, but the polynomial ring over the integers fails to be a PIR; if R = Z[x] denotes the polynomial ring over the integers, I = 2 · R + X · R is an ideal which cannot be generated by a single element. Despite this counterexample, the polynomial ring over any field is always a principal ideal domain and in fact, a Euclidean domain. More generally, a polynomial ring is a PID if and only if the polynomial ring in question is over a field.

Aside from the polynomial ring over a PIR, principal ideal rings possess many interesting properties due to their connection with the integers in terms of divisibility; that is, principal ideal domains behave similarly to the integers with respect to divisibility. For example, any PID is a UFD; i.e, an analogue of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic holds for principal ideal domains. Furthermore, since Noetherian rings are precisely those rings in which any ideal is finitely generated, principal ideal domains are trivially Noetherian rings. The fact that irreducible elements coincide with prime elements for PID's, together with the fact that every PID is Noetherian, implies that any PID is a UFD. One can also speak of the greatest common divisor of two elements in a PID; if x and y are elements of R, a principal ideal domain, then x · R + y · R = c · R for some c in R since the left-hand side is indeed an ideal. Therefore, c is the desired "GCD" of x and y.

An important class of rings lying in between fields and PID's, is the class of Euclidean domains. In particular, any field is a Euclidean domain, and any Euclidean domain is a PID. An ideal in a Euclidean domain is generated by any element of that ideal with minimum degree (all such elements must be associate). However, not every PID is a Euclidean domain; the ring ![\Bbb{Z}\left[\frac{1+\sqrt{-19}}{2}\right]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/348718f01af0d987f73c58815fd1be33.png) furnishes a counterexample.

furnishes a counterexample.

Unique factorization domains

The theory of unique factorization domains (UFD) also forms an important part of ring theory. In effect, a unique factorization domain is ring in which an analogue of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic holds. Formally,

Definition

Let R be a ring. Then R is said to be a unique factorization domain (abbreviated UFD), if the following conditions are satisfied:

1. R is an integral domain.

2. Every non-zero non-unit of R is the product of a finite number of irreducible elements.

3. If  =

=  , where all ai's and bj's are irreducible, then n = m and after possible renumbering of the ai's and bj's, bi = ai · ui where ui is a unit in R.

, where all ai's and bj's are irreducible, then n = m and after possible renumbering of the ai's and bj's, bi = ai · ui where ui is a unit in R.

The second condition above guarantees that "non-trivial" elements of R can be decomposed into irreducibles, and according to the third condition, such a finite decomposition is unique "up to multiplication by unit elements." This weakened form of uniqueness is reasonable to assume for otherwise even the integers would not satisfy the properties of being a UFD ((-2)2 = 22 = 4 demonstrates two "distint" decompositions of 4; however both decompositions of 4 are equivalent up to multiplication by units (-1 and +1)). The fact that the integers constitute a UFD follows from the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

For arbitrary rings, one may define a prime element and an irreducible element; these two may not in general coincide. However, a prime element in a domain is always irreducible. For UFD's, irreducible elements are also primes.

The class of unique factorization domains is related to other classes of rings. For instance, any Noetherian domain satisfies conditions 1 and 2 above, but in general Noetherian domains fail to satisfy condition 3. However, if the set of prime elements and the set of irreducible elements coincide for a Noetherian domain, the third condition of a UFD is satisfied. In particular, principal ideal domains are UFD's.

Integral domains and fields

While rings are very important mathematical objects, there are a lot of restrictions involved in their theory. For instance, suppose we have a ring R and suppose a and b are in R. If a is non-zero and a · b = 0, then b need not necessarily be 0. In particular, if a · b = a · c with a non-zero b need not equal c. An example of this is the set of n x n matrices over R where a maybe such a non-zero matrix but may be singular. In this case, the result may not be true. However, we can impose additional conditions on the ring to ensure that this be true; namely make the ring into an integral domain (that is a non-trivial commutative ring with no zero divisors). But we still run into a problem; namely we can't necessarily divide by non-zero elements. For example, the collection of all integers form an integral domain but we still can't divide an integer a by another integer b. For example, 2 cannot divide 3 to obtain another element in this ring. However, this problem can readily be solved if we ensure that every element in the ring has a multiplicative inverse. A field is a ring in which the non-zero elements form an abelian group under multiplication. In particular, a field is an integral domain (and therefore has no zero divisors) along with an additional operation of 'division'. Namely, if a and b are in a field F, then a/b is defined to be a · b−1 which is well defined.

Formal definition

Let (R, +, · ) be a ring. Then (R, +, · ) is said to be an integral domain if (R, +, · ) is commutative and has no zero divisors. Furthermore, (R, +, · ) is said to be a field, if its non-zero elements form an abelian group under multiplication.

Note

- If we require that the zero element (0) in a ring to have a multiplicative inverse, then the ring must be trivial.

Examples

- The integers form a commutative ring under the natural operations of addition and multiplication. In fact, the integers form what is known as an integral domain (a commutative ring with no zero divisors).

- A ring whose non-zero elements form an abelian group under multiplication (not just a commutative monoid), is called a field. So every field is an integral domain and every integral domain is a commutative ring. Furthermore, any finite integral domain is a field.

Relation to other algebraic structures

The following is a chain of class inclusions that describes the relationship between rings, domains and fields:

- Commutative rings ⊃ integral domains ⊃ half factorization domains ⊃unique factorization domains ⊃ principal ideal domains ⊃ Euclidean domains ⊃ fields

Fields and integral domains are very important in modern algebra.

Noncommutative rings

The study of noncommutative rings is a major area in modern algebra; especially ring theory. Often noncommutative rings possess interesting invariants that commutative rings do not. As an example, there exist rings which contain non-trivial proper left or right ideals, but are still simple; that is contain no non-trivial proper (two-sided) ideals. This example illustrates how one must take care when studying noncommutative rings because of possible counterintuitive misconceptions.

The theory of vector spaces is one illustration of a special case of an object studied in noncommutative ring theory. In linear algebra, the "scalars of a vector space" are required to lie in a field - a commutative division ring. The concept of a module, however, requires only that the scalars lie in an abstract ring. Neither commutativity nor the division ring assumption is required on the scalars in this case. Module theory has various applications in noncommutative ring theory, as one can often obtain information about the structure of a ring by making use of its modules. The concept of the Jacobson radical of a ring; that is, the intersection of all right/left annihilators of simple right/left modules over a ring, is one example. The fact that the Jacobson radical can be viewed as the intersection of all maximal right/left ideals in the ring, shows how the internal structure of the ring is reflected by its modules. It is also remarkable that the intersection of all maximal right ideals in a ring is the same as the intersection of all maximal left ideals in the ring, in the context of all rings; whether commutative or noncommutative. Therefore, the Jacobson radical also captures a concept which may seem to be not well-defined for noncommutative rings.

Noncommutative rings serve as an active area of research due to their ubiquity in mathematics. For instance, the ring of n by n matrices over a field is noncommutative despite its natural occurrence in physics. More generally, endomorphism rings of abelian groups are rarely commutative.

Noncommutative rings, like noncommutative groups, are not very well understood. For instance, although every finite abelian group is the direct sum of (finite) cyclic groups of prime-power order, non-abelian groups do not possess such a simple structure. Likewise, various invariants exist for commutative rings, whereas invariants of noncommutative rings are difficult to find. As an example, the nilradical, although "innocent" in nature, need not be an ideal unless the ring is assumed to be commutative. Specifically, the set of all nilpotent elements in the ring of all n x n matrices over a division ring never forms an ideal, irrespective of the division ring chosen. Therefore, the nilradical cannot be studied in noncommutative ring theory. Note however that there are analogues of the nilradical defined for noncommutative rings, that coincide with the nilradical when commutativity is assumed.

One of the best known noncommutative rings is the division ring of quaternions.

Category theoretical description

Every ring can be thought of as monoids in Ab, the category of abelian groups (thought of as a monoidal category under the tensor product). The monoid action of a ring R on a abelian group is simply an R-module. Essentially, an R-module is a generalization of the notion of a vector space - where rather than a vector space over a field, one has a "vector space over a ring".

Let (A, +) be an abelian group and let End(A) be its endomorphism ring (see above). Note that, essentially, End(A) is the set of all morphisms of A, where if f is in End(A), and g is in End(A), the following rules may be used to compute f + g and f · g:

- (f + g)(x) = f(x) + g(x)

- (f · g)(x) = f(g(x))

where + as in f(x) + g(x) is addition in A, and function composition is denoted from right to left. Therefore, associated to any abelian group, is a ring. Conversely, given any ring, (R, +, · ), (R, +) is an abelian group. Furthermore, for every r in R, right (or left) multiplication by r gives rise to a morphism of (R, +), by right (or left) distributivity. Let A = (R, +). Consider those endomorphisms of A, that "factor through" right (or left) multiplication of R. In other words, let EndR(A) be the set of all morphisms m of A, having the property that m(r · x) = r · m(x). It was seen that every r in R gives rise to a morphism of A - right multiplication by r. It is in fact true that this association of any element of R, to a morphism of A, as a function from R to EndR(A), is an isomorphism of rings. In this sense, therefore, any ring can be viewed as the endomorphism ring of some abelian X-group (by X-group, it is meant a group with X being its set of operators)[14]. In essence, the most general form of a ring, is the endomorphism group of some abelian X-group.

See also

- Ring theory

- Glossary of ring theory

- Category of rings

- Algebra over a commutative ring

- Nonassociative ring

- Algebraic structure

- Chinese remainder theorem

- Semiring

- Special types of rings:

- Boolean ring

- Commutative ring

- Ordered ring

- Noetherian and artinian rings

- Dedekind ring

- Differential ring

- Division ring (skew field)

- Exponential ring

- Field

- Integral domain (ID)

- Local ring

- Principal ideal domain (PID)

- Reduced ring

- Regular ring

- Unique factorization domain (UFD)

- Valuation ring and discrete valuation ring

- Zero ring

Notes

^ a: Some authors only require that a ring be a semigroup under multiplication; that is, do not require that there be a multiplicative identity (1). See the section Notes on the definition for more details.

^ b: Elements which do have multiplicative inverses are called units, see Lang 2002, §II.1, p. 84.

^ c: The closure axiom is already implied by the condition that +/• be a binary operation. Some authors therefore omit this axiom. Lang 2002

^ d: The transition from the integers to the rationals by adding fractions is generalized by the quotient field.

^ e: Many authors include commutativity of rings in the set of ring axioms (see above) and therefore refer to "commutative rings" as just "rings".

Citations

- ↑ Herstein 1964, §3, p. 83

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 [1]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lang 2005, App. 2, p. 360

- ↑ Herstein 1975, §2.1, p. 27

- ↑ Herstein, I. N. Topics in Algebra, Wiley; 2 edition (June 20, 1975), ISBN 0-471-01090-1.

- ↑ Joseph Gallian (2004), Contemporary Abstract Algebra, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 9780618514717

- ↑ Neal H. McCoy (1964), The Theory of Rings, The MacMillian Company, pp. 161, ISBN 978-1124045559

- ↑ Raymond Louis Wilder (1965), Introduction to Foundations of Mathematics, John Wiley and Sons, p. 176

- ↑ Lang 2005, §II.1, p. 90

- ↑ Cohn, Harvey (1980), Advanced Number Theory, New York: Dover Publications, pp. 49, ISBN 9780486640235

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 86, footnote 1.

- ↑ Jacobson 1945

- ↑ Pinter-Lucke 2007

- ↑ Jacobson (2009), p. 162, Theorem 3.2.

References

General references

- R.B.J.T. Allenby (1991), Rings, Fields and Groups, Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN 0-340-54440-6

- Atiyah M. F., Macdonald, I. G., Introduction to commutative algebra. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Reading, Mass.-London-Don Mills, Ont. 1969 ix+128 pp.

- Beachy, J. A. Introductory Lectures on Rings and Modules. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- T.S. Blyth and E.F. Robertson (1985), Groups, rings and fields: Algebra through practice, Book 3, Cambridge university Press, ISBN 0-521-27288-2

- Dresden, G. "Small Rings." [2]

- Ellis, G. Rings and Fields. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Goodearl, K. R., Warfield, R. B., Jr., An introduction to noncommutative Noetherian rings. London Mathematical Society Student Texts, 16. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989. xviii+303 pp. ISBN 0-521-36086-2

- Herstein, I. N., Noncommutative rings. Reprint of the 1968 original. With an afterword by Lance W. Small. Carus Mathematical Monographs, 15. Mathematical Association of America, Washington, DC, 1994. xii+202 pp. ISBN 0-88385-015-X

- Jacobson, Nathan (2009), Basic algebra, 1 (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-47189-1

- Nagell, T. "Moduls, Rings, and Fields." §6 in Introduction to Number Theory. New York: Wiley, pp. 19–21, 1951

- Nathan Jacobson, Structure of rings. American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications, Vol. 37. Revised edition American Mathematical Society, Providence, R.I. 1964 ix+299 pp.

- Nathan Jacobson, The Theory of Rings. American Mathematical Society Mathematical Surveys, vol. I. American Mathematical Society, New York, 1943. vi+150 pp.

- Kaplansky, Irving (1974), Commutative rings (Revised ed.), University of Chicago Press, MR0345945, ISBN 0226424545

- Lam, T. Y., A first course in noncommutative rings. Second edition. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 131. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2001. xx+385 pp. ISBN 0-387-95183-0

- Lam, T. Y., Exercises in classical ring theory. Second edition. Problem Books in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, New York, 2003. xx+359 pp. ISBN 0-387-00500-5

- Lam, T. Y., Lectures on modules and rings. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 189. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1999. xxiv+557 pp. ISBN 0-387-98428-3

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 211 (Revised third ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1878556, ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4

- Lang, Serge (2005), Undergraduate Algebra (3rd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-22025-3.

- Matsumura, Hideyuki (1989), Commutative Ring Theory, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36764-6

- McConnell, J. C.; Robson, J. C. Noncommutative Noetherian rings. Revised edition. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 30. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2001. xx+636 pp. ISBN 0-8218-2169-5

- Pinter-Lucke, James (2007), "Commutativity conditions for rings: 1950–2005", Expositiones Mathematicae 25 (2): 165–174, doi:10.1016/j.exmath.2006.07.001, ISSN 0723-0869

- Rowen, Louis H., Ring theory. Vol. I, II. Pure and Applied Mathematics, 127, 128. Academic Press, Inc., Boston, MA, 1988. ISBN 0-12-599841-4, ISBN 0-12-599842-2

- Sloane, N. J. A. Sequences A027623 and A037234 in "The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

- Zwillinger, D. (Ed.). "Rings." §2.6.3 in CRC Standard Mathematical Tables and Formulae. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, pp. 141–143, 1995

Special references

- Balcerzyk, Stanisław; Józefiak, Tadeusz (1989), Commutative Noetherian and Krull rings, Ellis Horwood Series: Mathematics and its Applications, Chichester: Ellis Horwood Ltd., ISBN 978-0-13-155615-7

- Balcerzyk, Stanisław; Józefiak, Tadeusz (1989), Dimension, multiplicity and homological methods, Ellis Horwood Series: Mathematics and its Applications., Chichester: Ellis Horwood Ltd., ISBN 978-0-13-155623-2

- Ballieu, R. "Anneaux finis; systèmes hypercomplexes de rang trois sur un corps commutatif." Ann. Soc. Sci. Bruxelles. Sér. I 61, 222-227, 1947.

- Berrick, A. J. and Keating, M. E. An Introduction to Rings and Modules with K-Theory in View. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Eisenbud, David (1995), Commutative algebra. With a view toward algebraic geometry., Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 150, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR1322960, ISBN 978-0-387-94268-1; 978-0-387-94269-8

- Fine, B. "Classification of Finite Rings of Order ." Math. Mag. 66, 248-252, 1993

- Fletcher, C. R. "Rings of Small Order." Math. Gaz. 64, 9-22, 1980

- Fraenkel, A. "Über die Teiler der Null und die Zerlegung von Ringen." J. reine angew. Math. 145, 139-176, 1914

- Gilmer, R. and Mott, J. "Associative Rings of Order ." Proc. Japan Acad. 49, 795-799, 1973

- Harris, J. W. and Stocker, H. Handbook of Mathematics and Computational Science. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1998

- Jacobson, Nathan (1945), "Structure theory of algebraic algebras of bounded degree", Annals of Mathematics (Annals of Mathematics) 46 (4): 695–707, doi:10.2307/1969205, ISSN 0003-486X, http://jstor.org/stable/1969205

- Knuth, D. E. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, 3rd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1998

- Korn, G. A. and Korn, T. M. Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: Dover, 2000

- Nagata, Masayoshi (1962), Local rings, Interscience Tracts in Pure and Applied Mathematics, 13, Interscience Publishers, pp. xiii+234, MR0155856, ISBN 978-0-88275-228-0 (1975 reprint)

- Pierce, Richard S., Associative algebras. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 88. Studies in the History of Modern Science, 9. Springer-Verlag, New York–Berlin, 1982. xii+436 pp. ISBN 0-387-90693-2

- Zariski, Oscar; Samuel, Pierre (1975), Commutative algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 28, 29, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0387900896

Historical references

- History of ring theory at the MacTutor Archive

- Birkhoff, G. and Mac Lane, S. A Survey of Modern Algebra, 5th ed. New York: Macmillian, 1996

- Bronshtein, I. N. and Semendyayev, K. A. Handbook of Mathematics, 4th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2004. ISBN 3-540-43491-7

- Faith, Carl, Rings and things and a fine array of twentieth century associative algebra. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 65. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 1999. xxxiv+422 pp. ISBN 0-8218-0993-8

- Itô, K. (Ed.). "Rings." §368 in Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mathematics, 2nd ed., Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986

- Kleiner, I. "The Genesis of the Abstract Ring Concept." Amer. Math. Monthly 103, 417-424, 1996

- Renteln, P. and Dundes, A. "Foolproof: A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor." Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 52, 24-34, 2005

- Singmaster, D. and Bloom, D. M. "Problem E1648." Amer. Math. Monthly 71, 918-920, 1964

- Van der Waerden, B. L. A History of Algebra. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1985

- Wolfram, S. A New Kind of Science. Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media, p. 1168, 2002

![[x + y, z] = [x, z] + [y, z], \quad [z, x + y] = [z, x] + [z, y]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/612225aa111eef27437e38b56c4eb4b3.png)

![[x,[y,z]] + [y,[z,x]] + [z,[x,y]] = 0 \quad](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/69ee53d21fe7eb5e7b8ed7938cb8cab0.png)

![[x,x]=0 \quad](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/4b3d4565edeb5d1f29e91ea7b7e4655b.png)